With a name like “The Good Terrorist,” how can it not be good? Of course, for the well-to-do reading this, such words are avoided entirely. “Terrorists are bad, for god’s sake! The government told me so! I avoid anything that TV tells me is bad.”

Doris Lessing’s “The Good Terrorist” is sure to grab people’s attention at the dinner table if conversation becomes too dull to bear. Although, the story itself doesn’t quite live up to the title. Sure! Terrorism does take place, and it is pretty gruesome in the effects it has both on the main characters and bystanders. But the story is not so much about terrorism as it about a microcosm within a radical’s journey toward full and utter war against capitalism, and the misguided notions that too often worm their way in.

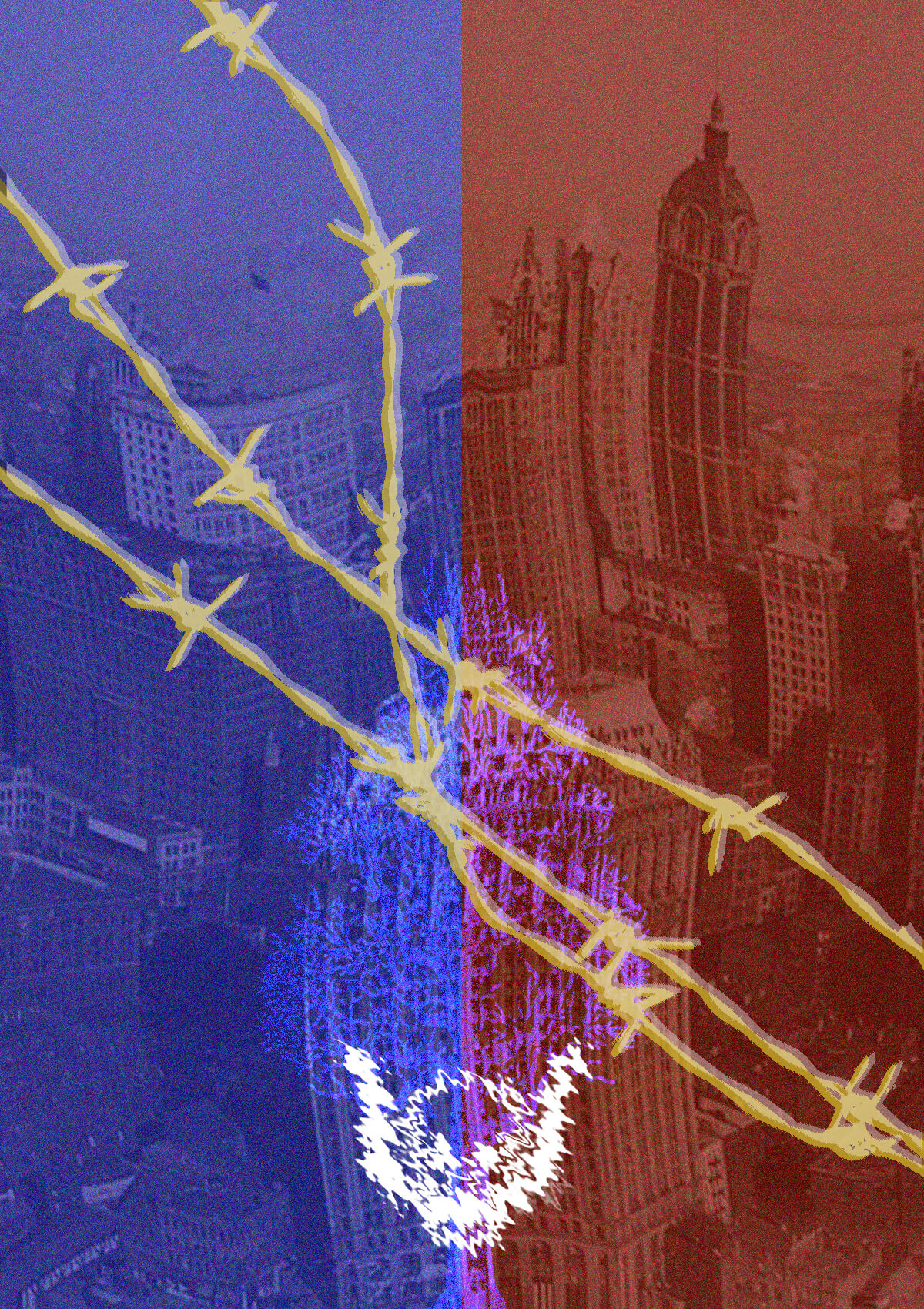

The general consciousness influenced by TV and almost unexplainable internet fads has little perception of “revolutionaries” outside the revolutionary actions themselves. Bridges are bombed. Embassies taken hostage. Dictators overthrown. Little attention is given to the interpersonal aspects of radical groups and the lifestyles that emerge. Much less, the diversity of personalities within radical groups. Even within radical circles, and the literature that’s passed around, this image can be lost. We end up focusing too much on the theory and action, and not the interpersonal day-to-day weaved throughout them. We fail to connect our interpersonal progress to the range of actions we are able to take.

The story follows the activities of Alice, a young British girl well versed in squatting and a member of a small communist party. Attached to her partner Jasper; their relationship is more reminiscent of a younger sibling to an older one, than a romantic partnership of equals. Jasper is a radical of questionable enthusiasm. More interested in the adrenaline of street fights, and the bragging rights of being arrested, than more substantive work that larger radical groups require. It’s here, in Alice’s relationship with Jasper that we begin to smell the beginnings of toxic social practices.

As was, and to a degree still is, prominent in past radical circles, women are often relegated to domestic, generally more feminine-coded activities. Even though these tasks are important and necessary for a successful group, hetereosexual male radicals will discount and ignore them. This is clearly evident in how the rest of Alice’s group looks down on her for caring about the state of the house they’re squatting in. Many of her comrades live in purposeful squalor, as if cleanliness, running water, and a functioning home mean nothing. They begrudgingly help on only the most physically intensive projects. All the while, failing to acknowledge Alice’s efforts in making their lives a little less erratic.

Although Alice’s efforts to fix up the squat can be tied to traditionally feminine roles, her motivation was more in line with creating a space with her own labor. As alienated objects within capitalism, we rarely see and experience the full results of our labor. It’s one reason why we’re so obsessed with creating our own unique living spaces and identities. We want to put in the effort and see the full spectrum of the labor we put in.

Sometimes, the naive radicals among us can misinterpret the desire for comfortable living quarters as consumeristic. A byproduct of ingrained capitalist advertising and bourgeoisie expectations. To a degree that definitely happens. But just because we’re against the excesses of capitalism and its injustices, doesn’t mean we must live spartan lifestyles.

Joy is such a rare experience these days, thanks to the physical and mental intensity of the labor system, that many times the main source of joy is going home to a familiar and personalized living space.

Alice’s preoccupation with getting bare necessities in the house is met by her comrades as a bourgeoisie obsession with comforts. An asinine assumption, to say the least. There’s nothing romantic or praiseworthy about asceticism. Millions of people live without running water, much less clean water. Just as many live without homes, because this planet-wide system of accumulation deams them unworthy of basic shelter. Comfort isn’t bourgeoisie. If anything, the mass promotion of basic comforts is a revolutionary concept, because it’s constantly denied to us in the name of the rich getting richer.

As a kid, I enjoyed building forts and structures with my siblings and friends. We had full control of the design, implementation, and usage. In effect, we had total control over our labor. We could take pride in our accomplishments because we had responsibility for each stage, and its upkeep. I see this same concept in Alice’s workings on the house. Her efforts were not defined by the rigid gender roles of a patriarchal society, but communicated a form of actualization. A joy in taking full responsibility for something that was neglected by the powers at be.

Squatting is an explicit attack on spectacle capitalism. Where the spectacle creates elaborate mental and physical labyrinthes to acquiring basic necessities, squatting goes straight for the goods (as does stealing). Houses lay empty for a variety of selfish and petty reasons – all aimed to enrich capitalists. Plenty of people need housing, having been systematically exhumed from the housing system. Therefore, the houses should be taken; re-appropriated for the needs of the people.

Alice approaches squatting in wholesome terms, whereas her comrades approach squatting the same way a capitalist approaches housing. It’s expendable. After all her work on making the house decent, the others flippantly declare that they can just move to another squat to avoid the police. The life of a squatter is not legal, much less stable (in typical middle class terms), but the flippancy with which they treat the house implies a deeper issue. An issue that will continue to sabotage their efforts.

Jasper has to be the most detestable character in the whole book. Not only because he comes across as an adrenaline junky who read Marx once, but because he treats Alice in the most contemptible ways.

Like all good adrenaline junky radicals, his ideas and commands are sacred and his actions beyond critique.

Adrenaline junkies aren’t known for their critical thinking skills, seeing as they’re always looking for the next hit. Jasper’s uselessness as anything other than a stunt boy continually flies over his head. His thick-headed partner in crime and him are continually denied access into various sleeper cells, despite living next to one (something I don’t think they ever realized). Strategy, patience, rationalism, and nuance aren’t friends of his. Lots of talk of revolution, but somehow can’t move past attacking cops for the sake of attacking cops.

Like most adrenaline junkies, Jasper has plenty of toxic masculinity to go around. At moments, it’s implied he’s bisexual, or at least plays around with men when he runs off for days on end. But characteristics like that only ended up exasperating the overall toxicness of Jasper’s character. Running off for days on end – usually after a fight with Alice – is a sign of Jasper’s childish masculinity and need for excitement to the detriment of everyone around him. When he can’t control Alice with his presence, he opts for distance. Classic emotional manipulation: if I don’t get my way, you don’t get me.

Emotional manipulators proliferate in “The Good Terrorist.” Jasper is the masculine, dominating manipulator. Faye, represents the malicious use of mental health to control others.

The mentally fragile, yet incredibly erratic Faye exploits not only her partner, Roberta, but the rest of the squat. It’s a succinct picture of what happens when mental health issues are placated, not treated.

Roberta, Faye’s romantic partner, is reduced to apologizing for Faye every time she creates discord in the group, and coaxing her down off the edge. Alice is eventually pulled into this loop to give Roberta time away from Faye, to see her dying mother.

The dynamics between the squat members is a great example of why ideological alignment alone won’t make your roommates/comrades and you get along. Personalities must click. At the very least, they shouldn’t operate on abusive behaviors and patterns encouraged by hierarchical capitalist society. Unfortunately, everyone cannot, and should not, be accepted into living spaces without regard for behavior or chemistry. For the sanity and wellbeing of everyone.

Interpersonal relations go beyond the boundaries of the present. They spill into the past as well. Alice’s past is made up of her parents, who she can’t seem to shake off. Her feelings are a mixture of disgust, hatred, love, and nostalgia. Despite hurting her parents multiple times, she always comes back with sympathy and love for them.

Alice’s mother represents the most pressing intersection of contradicting feelings. She has stolen from her mother, taken advantage of her hospitality by staying at her mother’s place for months with Jasper, and been unnecessarily mean to her. But when Alice sees the downsizing her mom had to make to live within her means, she is filled with injustice at her mom’s predicament. Ironically enough, her mom would’ve been able to keep the original apartment if it weren’t for Alice taking advantage of her for room and board.

It’s this disconnect between disgust for her parent’s middle class, petty-bourgeoisie status, and frustrated shock at their subsequent downgrade in housing and lifestyle that gives us insight into the person Alice still is. For all her talk of revolution and revolt, she never expects her parents to change for the worst. She is naive to their true economic precarity. They’re not living in squats, or solidly working class, sure. Yet, all it takes is a few missteps, all thanks to their daughter, to pull down the curtain of middle class comfort and security.

We may despise our parents for what they’ve done and what they represent. But underestimating their economic precarity will only end up exacerbating our childhood delusions.

Alice, to a degree, but much less than the child-games of Jasper and Bert, is playing the role of a radical. Her parents represent her past; a past she is now in open opposition to. Her fellow revolutionaries and her are playing a game, a game that doesn’t require substantive work (like building dual power in the form of mutual aid, community defense, jail support, housing support, and so on). It relies on images of the revolution. A lifestyle of what a revolutionary should look like. This is how they can participate in street brawls and pickets with cops like the cinema and mall is to the middle class. Ultimately killing innocent people in a brash and senseless display of the revolutionary spectacle: terrorism.

In a poignant moment of self-awareness, Alice’s mother accuses her of the same rigid gender norms that held her back:

“‘I haven’t done anything with my life,’ she was even smiling, contemptuous, as she negated Alice in this way. ‘I used to look at you when you were little, and I thought, well, at least I’ll make sure that Alice gets educated, she’ll be equipped. I won’t have Alice stuck in my position, no qualifications for anything. But it turned out that you spend your life exactly as I did. Cooking and nannying for other people. An all-purpose female drudge.’”

It’s not completely fair to denigrate Alice’s actions to the role of a mere house wife. Yet, this moment strikes me hard. Alice’s mother is, for me, that self-deprecative voice hell-bent on questioning every self-improvement. You really haven’t progressed past your past self. You’ve only hid it better from yourself. It’s a disturbing thought for everyone, but especially for the heartfelt radical, to contemplate the possibility that those two steps forward were actually three steps back.

Just when it’s thought that Alice’s mother has done her worst, she moves in for the kill shot: hopelessness, mixed with pessimism.

“‘This world is run by people who know how to do things. They know how things work. They are equipped. Up there, there’s a layer of people who run everything. But we – we’re just peasants. We don’t understand what’s going on, and we can’t do anything… Oh you, running about playing revolutions, playing little games, thinking you’re important. You’re just peasants, you’ll never do anything.’”

First, question that they’re even going anywhere. Then, convince them any potential for change is impossible. It’s a classic reaction of the Euro-Amerikan settler.

Her mother’s words hurt to read (again, self-deprecation!), but they’re just as easily dissected, separated, and defeated.

The benefactors of empire – no matter how little they actually benefit from it all – must rely on hopeless pessimism. It’s one of many psychological defense mechanisms used to obstruct and incapacitate change. Why do you think every basic-ass logic-bro, who took one remedial economics class in highschool, has to say that socialism will never work and has never worked? Why do most people discount and demonize “socialist” policy stances, like a livable wage, universal healthcare, nationalization, and so on? Partly because they’ve been lied to, fed a narrative of inefficiency and failure that are only half-truths. But largely – for a lot of middle class adherents – because these regurgitators see themselves as inheritors of the wealth, prestige, and opportunities afforded to only the most connected and well-off of Euro-Amerikan settlers.

In a twisted set of rules, the hopeful are labeled pessimistic and hopeless by the very consumers of defeatist joylessness. “Why must you be so negative?” said the habitual killjoy.

We must remember that self-deprecation and self-deception are separate issues. The former does not necessitate the latter. It’s here, when faced with the likes of Alice’s mother, that we must immediately shut down the barbaric reactionary pessimism. Like Alice, we must declare, “But you just wait. Everything is rotten. It’s all undermined. But you’re so dozy and stupid and you can’t even see it. We are going to pull it all down.”